J. J. Thomson

| J. J. Thomson | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 18 December 1856 Cheetham Hill, Manchester, UK |

| Died | 30 August 1940 (aged 83) Cambridge, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | Cambridge University |

| Alma mater | University of Manchester University of Cambridge |

| Academic advisors | John Strutt (Rayleigh) Edward John Routh |

| Notable students | Charles Glover Barkla Charles T. R. Wilson Ernest Rutherford Francis William Aston John Townsend J. Robert Oppenheimer Owen Richardson William Henry Bragg H. Stanley Allen John Zeleny Daniel Frost Comstock Max Born T. H. Laby Paul Langevin Balthasar van der Pol Geoffrey Ingram Taylor |

| Known for | Plum pudding model Discovery of electron Discovery of isotopes Mass spectrometer invention First m/e measurement Proposed first waveguide Thomson scattering Thomson problem Coining term 'delta ray' Coining term 'epsilon radiation' Thomson (unit) |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize for Physics (1906) |

Signature |

|

|

Notes

Thomson is the father of Nobel laureate George Paget Thomson. |

|

Sir Joseph John “J. J.” Thomson, OM, FRS (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer. Thomson was awarded the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of the electron and for his work on the conduction of electricity in gases.

Contents |

Biography

Joseph John Thomson was born in 1856 in Cheetham Hill, Manchester, England. His mother, Emma Swindells, came from a local textile family. His father, Joseph James Thomson, ran an antiquarian bookshop founded by a great-grandfather from Scotland (hence the Scottish spelling of his surname). He had a brother two years younger than him, Frederick Vernon Thomson.[1]

His early education was in small private schools, and demonstrated great talent and interest in science. In 1870 he was admitted to Owens College. Being only 14 years old at the time, he was unusually young. His parents planned to enroll him as an apprentice engineer to Sharp-Stewart & Co., a locomotive manufacturer, but these plans were cut short when his father died in 1873.[1] He moved on to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1876. In 1880, he obtained his BA in mathematics (Second Wrangler and 2nd Smith's prize) and MA (with Adams Prize) in 1883.[2] In 1884 he became Cavendish Professor of Physics. One of his students was Ernest Rutherford, who would later succeed him in the post. In 1890 he married Rose Elisabeth Paget, daughter of Sir George Edward Paget, KCB, a physician and then Regius Professor of Physic at Cambridge. He fathered one son, George Paget Thomson, and one daughter, Joan Paget Thomson, with her. One of Thomson's greatest contributions to modern science was in his role as a highly gifted teacher, as seven of his research assistants and his aforementioned son won Nobel Prizes in physics. His son won the Nobel Prize in 1937 for proving the wavelike properties of electrons.

He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1906, "in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases." He was knighted in 1908 and appointed to the Order of Merit in 1912. In 1914 he gave the Romanes Lecture in Oxford on "The atomic theory". In 1918 he became Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, where he remained until his death. He died on August 30 1940 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to Sir Isaac Newton.

Thomson was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 12 June 1884 and was subsequently President of the Royal Society from 1915 to 1920.

Career

Discovery of the electron

Until 1897, scientists believed atoms were indivisible, the ultimate particles of matter, but Thomson proved them wrong when he discovered that atoms contained particles known as electrons. Thomson discovered this through his explorations on the properties of cathode rays. Thomson found that the rays could be deflected by an electric field (in addition to magnetic fields, which was already known). He concluded that these rays, rather than being waves, were composed of very light negatively charged particles which he called "corpuscles". (Later scientists preferred the name electron which had been suggested by George Johnstone Stoney in 1894, prior to Thomson's actual discovery).

Thomson believed that the corpuscles emerged from the atoms of the trace gas inside his cathode ray tubes. He thus concluded that atoms were divisible, and that the corpuscles were their building blocks. To explain the overall neutral charge of the atom, he proposed that the corpuscles were distributed in a uniform sea of positive charge; this was the plum pudding model as the electrons were embedded in the positive charge like plums in a plum pudding (although in Thomson's model they were not stationary).

Isotopes and mass spectrometry

In 1913, as part of his exploration into the composition of canal rays, Thomson channelled a stream of ionized neon through a magnetic and an electric field and measured its deflection by placing a photographic plate in its path. Thomson observed two patches of light on the photographic plate (see image on right), which suggested two different parabolas of deflection. Thomson concluded that neon is composed of atoms of two different atomic masses (neon-20 and neon-22), that is to say of two isotopes. This was the first evidence for isotopes of a stable element; Frederick Soddy had previously proposed the existence of isotopes to explain the decay of certain radioactive elements.

Thomson's separation of neon isotopes by their mass was the first example of mass spectrometry, which was subsequently improved and developed into a general method by Thomson's student F. W. Aston and by A. J. Dempster.

Other work

In 1905 Thomson discovered the natural radioactivity of potassium.[3]

In 1906 Thomson demonstrated that hydrogen had only a single electron per atom. Previous theories allowed various numbers of electrons.[4][5]

Experiments with cathode rays

Earlier, physicists debated whether cathode rays were immaterial like light ("some process in the aether") or had mass and were composed of particles. The aetherial hypothesis was vague, but the particle hypothesis was definite enough for Thomson to test.

First experiment

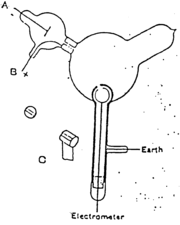

While supporters of the aetherial theory accepted the possibility that negatively-charged particles are produced in Crookes tubes, they believed that they are a mere byproduct and that the cathode rays themselves are immaterial. Thomson set out to investigate whether or not he could actually separate the charge from the rays.

Thomson constructed a Crookes tube with an electrometer set to one side, out of the direct path of the cathode rays. Thomson could trace the path of the ray by observing the phosphorescent patch it created where it hit the surface of the tube. Thomson observed that the electrometer registered a charge only when he deflected the cathode ray to it with a magnet. He concluded that the negative charge and the rays were one and the same.

Second experiment

In his second experiment, he investigated whether or not the rays could be deflected by an electric field. Previous experimenters had failed to observe this, but Thomson believed their experiments were flawed because their tubes contained too much gas.

Thomson constructed a Crookes tube with a near-perfect vacuum. At the start of the tube was the cathode from which the rays projected. The rays were sharpened to a beam by two metal slits - the first of these slits doubled as the anode, the second was connected to the earth. The beam then passed between two parallel aluminium plates, which produced an electric field between them when they were connected to a battery. The end of the tube was a large sphere where the beam would impact on the glass, created a glowing patch. Thomson pasted a scale to the surface of this sphere to measure the deflection of the beam.

When the upper plate was connected to the negative pole of the battery and the lower plate to the positive pole, the glowing patch moved downwards, and when the polarity was reversed, the patch moved upwards.

Third experiment

In his third experiment, Thomson measured the mass-to-charge ratio of the cathode rays by measuring how much they were deflected by a magnetic field and how much energy they carried. He found that the mass to charge ratio was over a thousand times lower than that of a hydrogen ion (H+), suggesting either that the particles were very light and/or very highly charged.

Conclusions

As the cathode rays carry a charge of negative electricity, are deflected by an electrostatic force as if they were negatively electrified, and are acted on by a magnetic force in just the way in which this force would act on a negatively electrified body moving along the path of these rays, I can see no escape from the conclusion that they are charges of negative electricity carried by particles of matter.—J. J. Thomson[6]

As to the source of these particles, Thomson believed they emerged from the molecules of gas in the vicinity of the cathode.

If, in the very intense electric field in the neighbourhood of the cathode, the molecules of the gas are dissociated and are split up, not into the ordinary chemical atoms, but into these primordial atoms, which we shall for brevity call corpuscles; and if these corpuscles are charged with electricity and projected from the cathode by the electric field, they would behave exactly like the cathode rays.—J. J. Thomson[6]

Thomson imagined the atom as being made up of these corpuscles swarming in a sea of positive charge; this was his plum pudding model. This model was later proved incorrect when Ernest Rutherford showed that the positive charge is concentrated in the nucleus of the atom.

Awards and recognition

- Royal Medal (1894)

- Hughes Medal (1902)

- Nobel Prize for Physics (1906)

- Elliott Cresson Medal (1910)

- Copley Medal (1914)

- Franklin Medal (1922)

In 1991 the thomson (symbol: Th) was proposed as a unit to measure mass-to-charge ratio in mass spectrometry.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Davis, J.J. Thomson and the Discovery of the Electron

- ↑ Thomson, Joseph John in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ Thomson, J. J. (1905). "On the emission of negative corpuscles by the alkali metals". Philosophical Magazine, Ser. 6 10: 584–590. doi:10.1080/14786440509463405.

- ↑ Hellemans, Alexander; Bryan Bunch (1988). The Timetables of Science. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 411. ISBN 0671621300.

- ↑ Thomson, J. J. (June 1906). "On the Number of Corpuscles in an Atom". Philosophical Magazine 11: 769–781. http://dbhs.wvusd.k12.ca.us/webdocs/Chem-History/Thomson-1906/Thomson-1906.html. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cathode rays Philosophical Magazine, 44, 293 (1897)

References

- 1883. A Treatise on the Motion of Vortex Rings: An essay to which the Adams Prize was adjudged in 1882, in the University of Cambridge. London: Macmillan and Co., pp. 146. Recent reprint: ISBN 0-5439-5696-2.

- 1888. Applications of Dynamics to Physics and Chemistry. London: Macmillan and Co., pp. 326. Recent reprint: ISBN 1-4021-8397-6.

- 1893. Notes on recent researches in electricity and magnetism: intended as a sequel to Professor Clerk-Maxwell's 'Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism'. Oxford Univ. Press, pp.xvi and 578. 1991, Cornell University Monograph: ISBN 1-4297-4053-1.

- 1921 (1895). Elements Of The Mathematical Theory Of Electricity And Magnetism. London: Macmillan and Co. Scan of 1895 edition.

- (with J.H. Poynting). A Text book of Physics in Five Volumes: Properties of Matter, Sound, Heat, Light, and Magnetism & Electricity.

- Navarro, Jaume, 2005, "Thomson on the Nature of Matter: Corpuscles and the Continuum," Centaurus 47(4): 259-82.

- Downard, Kevin, 2009. "J.J. Thomson Goes to America" J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20(11): 1964-1973. [1]

- Dahl, Per F., "Flash of the Cathode Rays: A History of J.J. Thomson's Electron". Institute of Physics Publishing. June, 1997. ISBN 0-7503-0453-7

- J.J. Thomson (1897), Cathode rays, Philosophical Magazine, 44, 293 — Discovery of the electron

- J.J. Thomson (1913), Rays of positive electricity, Proceedings of the Royal Society, A 89, 1-20 — Discovery of neon isotopes

- J.J. Thomson, ""On the Structure of the Atom: an Investigation of the Stability and Periods of Oscillation of a number of Corpuscles arranged at equal intervals around the Circumference of a Circle; with Application of the Results to the Theory of Atomic Structure," Philosophical Magazine Series 6, Volume 7, Number 39, pp 237–265. This paper presents the classical "plum pudding model" from which the Thomson Problem is posed.

- The Master of Trinity at Trinity College, Cambridge

- J.J. Thomson, The Electron in Chemistry: Being Five Lectures Delivered at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia (1923).

- Davis, Eward Arthur & Falconer, Isabel. J.J. Thomson and the Discovery of the Electron. 1997. 978-0748406968

External links

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Thomson, Joseph John. |

- The Discovery of the Electron

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 1906

- Annotated bibliography for Joseph J. Thomson from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Essay on Thomson life and religious views

- The Cathode Ray Tube site

- Notes on recent researches in electricity and magnetism Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. {Reprinted by} Cornell University Library Digital Collections

- Nobel Prize acceptance lecture (1906)

- Thomson's discovery of the isotopes of Neon

- Thomson Building Opening - The Leys School, Cambridge (1927)

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry Montagu Butler |

Master of Trinity College, Cambridge 1918–1940 |

Succeeded by George Macaulay Trevelyan |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||